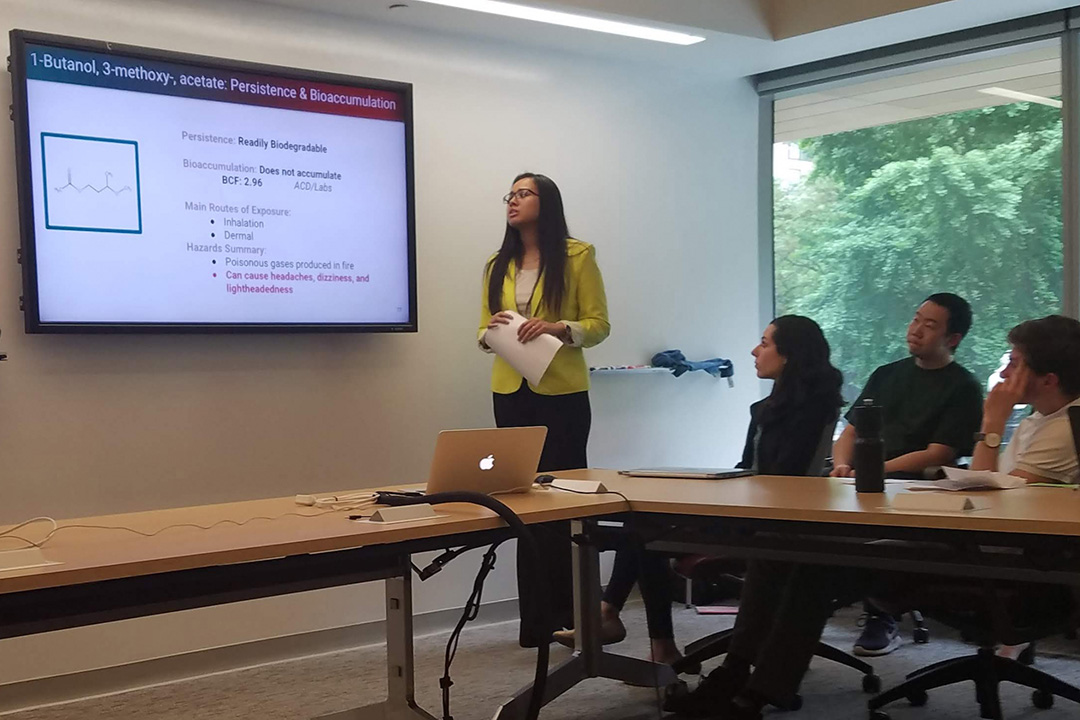

On May 8, students in the Chemical Toxicology and Safer Chemical Design course presented their final projects, which assessed hazard of 20 low-priority chemicals under the amended Toxic Substances Control Act, to key stakeholders in the DC area: United States Environmental Protection Agency, American Chemistry Council, Natural Resources Defense Council and the ACS Green Chemistry Institute. The class was a mix of undergraduate chemistry majors, doctoral chemistry students and master’s students from GWU’s new program in Environmental and Green Chemistry. This program offers a unique curriculum, focusing on safer chemical and process design, with the aim to train the next generation of chemists: those that can make chemicals the society needs but also understand that chemicals often have adverse effects on human and environmental health and how those effects can be mitigated by better design. For these students, the final presentations were more than just a class exercise – they were a validation of their new skillset in front of potential employers.

The students’ projects offered a critical survey of all the publicly available information about the 20 chemicals in question, including identifying critical data gaps such as those for chronic health endpoints like cancer, developmental toxicity, reproductive toxicity and neurotoxicity. In cases where important data gaps existed or for experimental studies with low reliability, the students applied accepted predictive toxicology tools and read-across approaches to help make informed decisions, showcasing their technical expert training. Understanding that chemicals cannot be assessed in isolation, the students’ decision as to whether to support the US EPA’s claim of low risk or challenge it also considered safety related to manufacturing processes and potential metabolites.

The presentations spanned nearly two hours, and offered tremendous value to the community since under the amended Toxic Substances Control Act and long-standing US EPA policies and guidance, the agency must have a defined minimum level of evidence to determine that a chemical is without risk of harm. For example, under its cancer guidelines, the US EPA needs data from male and female animals of at least two species in well-designed and conducted studies before it can determine that a chemical is not likely to be carcinogenic. Crucially, the assessments showed that a comprehensive assessment, which also considers functionality of these chemicals and potential safer alternatives on the market, cannot be reliable conducted by non-experts. Furthermore, it cannot be conducted by chemists or toxicologists alone; one must have solid training in both disciplines to tackle this challenge.

In the subsequent Q&A session, the students have gained a deeper and more realistic understanding of how chemical hazard information is used by lawmakers and regulatory agencies to make decisions that impact public health and environmental protection. Some people have jokingly said that making policy is like making sausage – information goes into a grinder and some mystery stuff comes out. To that end, this project helped lift the veil for the students on the process of turning science into policy. By understanding this extremely complicated process, it will help them in their future work to conduct research and provide expert opinions that will be most useful for policy decisions, hopefully with the goal of advancing safer and more sustainable chemistry.